Biochar and reclaiming urban soils

July 12, 2016 | By Admin |

Above image: Black Forest (29,930,000 tons), a land art installation using biochar created by former Nakano Associates staff member Hans Baumann, now residing in Los Angeles.

By Cayce James

The health and vitality of a living landscape can only be as good as that of the soil that hides beneath. Yet, more often than not, the soils we have to work with in urban environments have suffered a great deal of abuse. Either as part of previous development or with new construction, urban soils have typically been paved over, polluted, or torn up by the time they are ready for planting. The conventional approach to amending poor site soils is to add compost. However, the compaction, degradation and contamination that soils have undergone is often too extreme to be ameliorated through this method, making it necessary to import topsoil and truck off the existing soils. Especially on a large site, this is expensive and has significant environmental ramifications—existing soils are often landfilled, topsoil resources are further depleted, and lots of carbon is dumped into the atmosphere as soil is trucked on and off the site. Yet, compromising on soil quality to avoid these problems would only create new ones because healthy urban soils play an important role in filtering out stormwater pollutants.

What is needed are better methods for transforming poor and degraded soils into quality ones without wholesale replacement. Recent studies suggest that one material, biochar, has great potential in this regard. Though the name is somewhat new, the material is not. In fact, it has been used to amend soils in the Amazon basin for over 2,500 years. It has recently created a lot of buzz within the agricultural industry for its ability to improve soils and reduce atmospheric carbon. Less research has addressed the use of biochar in landscape soils, but initial studies have found promising results.

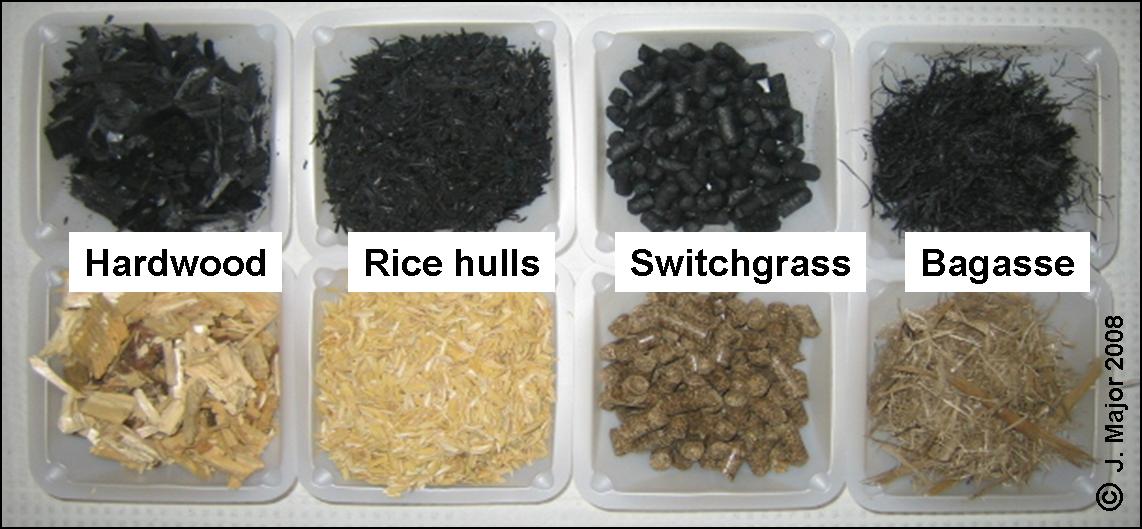

Biochar is created through a process called pyrolysis in which organic materials are heated in an low oxygen environment. Biochar can be created out of waste materials from agriculture, forestry, and food processing such as rice hulls, fruit pits, and wood chips.

Biochar feedstocks, Major 2008

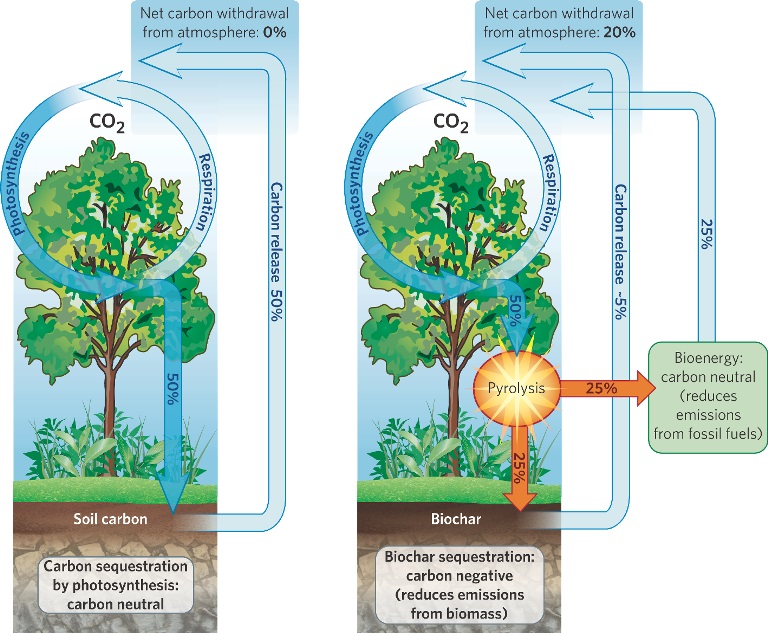

Further, the byproducts from creating biochar can be captured and used as bioenergy. Much of the carbon content of the biomass used in biochar production (that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere as CO2 through decomposition or burning) is sequestered within the biochar where it can remain stable for hundreds to thousands of years, making biochar a carbon negative product.

Biochar and carbon cycling, International Biochar Initiative

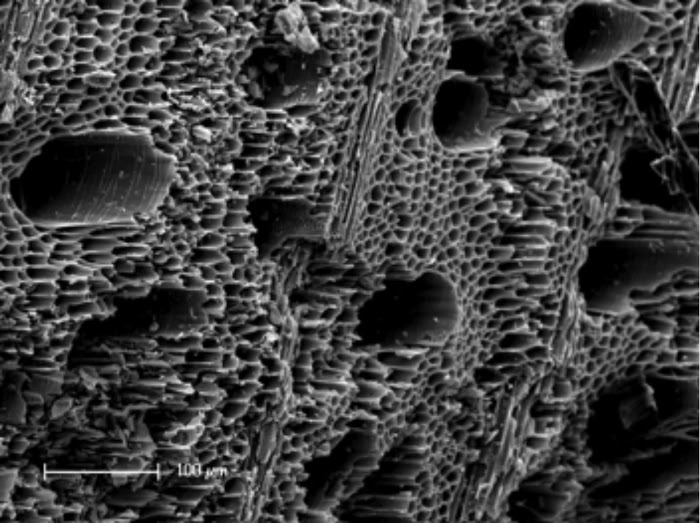

Biochar’s usefulness in improving soils stems from its structure. It is very porous with a lot of surface area. This structure allows biochar to hold water and nutrients in the soil like a sponge. The porosity of biochar also increases aeration in compacted soils and creates lots of microscopic nooks and crannies for soil biota to inhabit. On its own, biochar does not contain any nutrients. To be useful as a soil amendment, it needs to be activated by combining it with a nutrient source such as compost or fertilizer.

Biochar under a microscope, Brownsort, UK Biochar Research Centre

Biochar has also proven useful in other roles: it can reduce disease susceptibility in plants, and it is very effective at filtering and removing organic pollutants and heavy metals from stormwater and polluted soils. Biochar, however, does not seem to provide any measurable benefits when added to already healthy soils. (Fite and MacDonagh)

Soil test plots, Biochar.info

Research into biochar is still limited and sometimes controversial. Biochar can perform very differently based on the material it was created from. The endless variability of soil conditions combined with this variability of biochar itself provides a lot of room for further investigation. However, despite this variability, most urban soils are plagued by two basic problems—they are overly compacted and they lack organic matter. With biochar’s capacity for locking air and organic matter into the soil, these are two basic problems for which it may provide one very attractive solution. There are grounds for hope that biochar could transform the way we approach our urban landscapes.

To learn more, check out this great webinar, Biochar: What Designers Need to Know, by Kelby Fite, Ph.D. and Peter MacDonagh, FASLA

Here are some other good resources:

International Biochar Initiative

“Biochar: A ‘Miracle Product’ for Amending Soil?”

“Practical Applications of Biochar in the Landscape”

“Your Biochar Questions, Answered”